1. Linking with the Previous Article

In the previous article (“Change, Innovation and the School”) it was argued that:

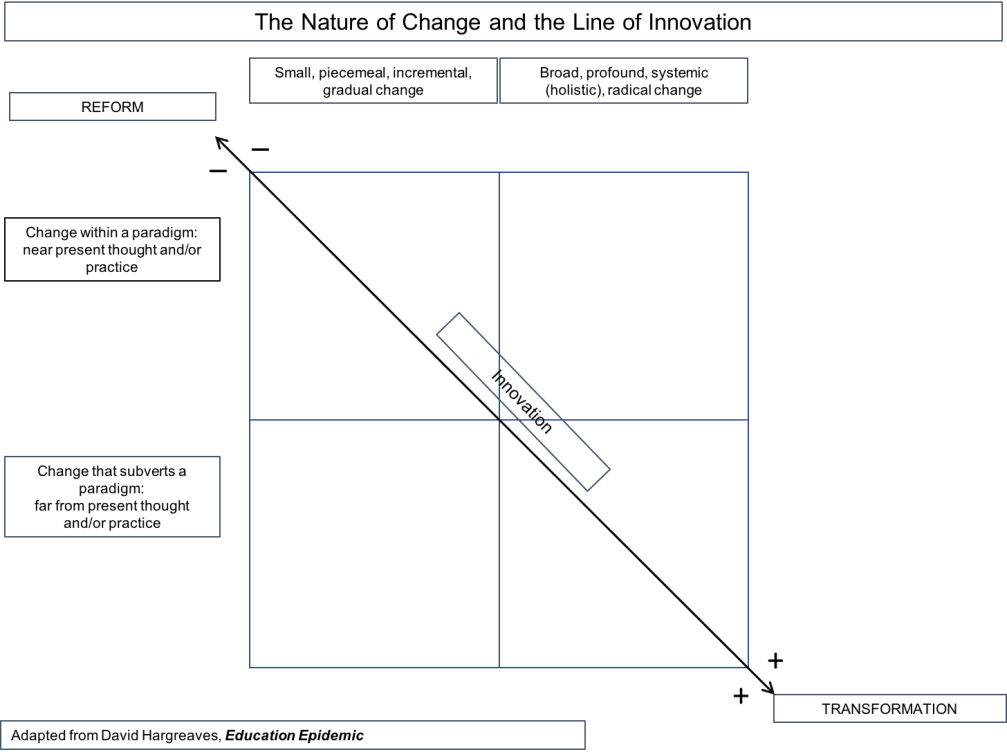

- Innovation involves change, but not every change brings innovation;

- Change can be ordinary (within the paradigm) or extraordinary (disruptive of the paradigm);

- Ordinary change is usually small, piecemeal, incremental, gradual, does not depart much from established thought or practice, and so leads at best to the improvement or reformation of an established paradigm; extraordinary change, on the other hand, is usually broad, deep, systemic (holistic), radical, departs considerably from established thought or practice, and so normally leads to the replacement or transformation of an established paradigm;

- It is the degree of innovation present in it (i.e., of that which, in it, is distinctly new) that differentiates extraordinary change from ordinary change;

- The amount, direction, rhythm and nature of the change that took place in the world in the past sixty five years or so are such as to require transformative change of every institution of society, including the school;

- The school, however, has been quite impervious and resistant to this requirement;

- Given the penetration of the conventional school in the social fabric, and given the strength of its attachment to the industrial paradigm, its reinvention in the direction of the paradigm outlined in the first article (Ubiquitous Education, or Society as the Learning Environment par excellence) will need to go through a transitional phase in which an Innovative School will help create the Learning Society (Society that Learns and where one Learns) and prepare us to actively, interactively and collaboratively learn in it.

The last article finished with a description of the main features of the Factory-Style School. This article will seek to describe the contours of the Innovative School, which will help pave the way for a world in which every institution of society will be educational (i.e., learning-oriented).

2. The Innovative School: Vision

To be innovative, a school must have a new vision, which includes a new understanding of its nature, mission, and values, as well as of the outcomes it seeks to achieve:

- Its nature must be inclusive: given the undeniable fact that we, humans, have multiple dimensions, and that other institutions of society are not presently capable of fully performing their educational tasks, the school needs to focus its attention on all of the dimensions of its students and help each of them develop as fully as possible as an integral and integrated human being;

- Its mission must be to create a learning environment where personalized education is possible and viable: given the undeniable fact that we, humans, are all different from one another in our personal characteristics, interests, talents, levels of motivation and learning styles, the school needs to pay special attention to each student in his specific uniqueness and make sure that he learns what he needs and wants to learn in the way and the rhythm in which he learns best;

- Its values must be:

- recognition of the fact that each student is a unique human being, worthy of full respect in his uniqueness by all those who work in the school;

- recognition of the fact that human beings develop through learning, that is, by building their capacity to do things which they were not capable of doing before;

- recognition of the fact that human beings learn best when they are actively engaged in doing things that are interesting to them (interest-based active learning, or learning by doing), in collaboration with partners who have similar interests (collaborative projects), and with the support of persons who can, when necessary, mediate the process and facilitate their learning;

- recognition of the fact that freedom is essential to the learning process, not only in the choice, by the students, of what to learn and of how to do it, but also in the organization of activities, by the school, in such a way as to provide unstructured time for leisure and otioseness (or idleness) on the part of the students (since intelligence does not prosper without a modicum of idleness and creativity does not prosper without a modicum of indiscipline);

- recognition of the fact that participation, by the students, in the elaboration of rules and in the making of decisions that affect their lives (including the processes in which they are evaluated) is essential for their learning and development.

- The Outcomes that it ought to pursue are:

- help the students define and choose a life project that combines their talents and their passions;

- help the students determine which competencies, skills, attitudes and values are required to transform their life project into reality and help them build, master or acquire them;

- maintain in the school a learning environment that is conducive to integral and integrated human development.

3. The Innovative School: Organizing Principles

To be innovative, a school must be built and function according to sound principles, such as these:

- To be innovative the school must contemplate broad and general learning expectations for the students (“curriculum“), personalizable for each student and flexible enough to be adjusted as the student develops, possibly changes interests, and defines and redefines his life project;

- To be innovative the school must adopt a flexible, student-centered learning methodology that is active, collaborative, problem-oriented, project-based and research-focused;

- To be innovative the school must make available to the students rich and abundant educational resources, including different types of digital technology, books, musical instruments, art material and material for art work, tools of various sorts, destined to all kinds of work, including manual labor, such as carpentry, woodwork, electronic / electric / automotive equipment repair, cooking, baking, restaurant and hotel work, etc.), and must allow these resources, and other resources that the students bring with them to the school (such as computers, tablets, smart phones, etc.) to be freely used by the students in their learning process;

- To be innovative the school must consider evaluation an essential part of the learning process, which cannot be dissociated from it, since evaluation is not a set of specific procedures applied at the end of the learning process to assess whether, or to what extent, the student learned what was expected of him;

- To be innovative the school must have a novel and modern modular architecture, and its spaces must be both generic and specialized but, in either case, flexible, modularizable, and reconfigurable, and its technology infrastructure must be state of the art;

- To be innovative the school must have a novel approach to time: time needs to regarded as something to be used flexibly. Business already adopts “flextime“: it is time the school does the same.

4. The Innovative School: Personnel

- To be innovative the school must have diverse personnel: professionals who have multiple talents and competencies to perform the general and specialized functions that are needed to address students with diversified and often rather special educational needs;

- To be innovative the school must count upon personnel committed to its vision of education and who are passionate for the work they do;

- To be innovative the school must select and recruit personnel who are not afraid to change and who want and feel comfortable to work in an student-centered innovative school that favors student initiative, protagonism and participation and that expects its professionals to be more like mentors, coaches, mediators and facilitators than like teachers and instructors.

5. Competencies, Curriculum, Methodology and Evaluation Procedures

Human beings, it was mentioned above, have multiple dimensions — at least the following: psychomotor, intellectual, social or interpersonal, affective or emotional, aesthetic or sensible, ethical and perhaps even spiritual. To fully develop these dimensions they need to develop and integrate multiple sets of competencies.

Competence is the capacity to mobilize, or draw upon, skills, knowledge and information (the thing the French call “savoirs”), attitudes, and values in order to perform (“savoir faire”) a set of tasks in a high level of proficiency and with some degree of automaticy.

Contrary to what is done in the school of the Industrial Era, in the innovative school competencies are the main ingredient of the curriculum, and conventional curricular contents (the traditional disciplines or subjects) are, to use a term the Brazilian National Curricular Parameters have made a household word, transversalized. These are drawn upon if and when needed. These contents are to be “pulled” by the students whenever they need or want them. It makes no sense to “push” them into the students just because they may eventually be needed or wanted.

That is why the curriculum of the innovative school must be a matrix of competencies rather than a grid of disciplines or subjects, dosed according to the age of the recipients.

The curriculum, in its broadest sense, is the total set of learning opportunities the school is willing to make available to its students.

Not every student needs to avail himself of every offering. This would be impossible, in the case where the offerings are ample, and it would rarely be recommendable, even when the offerings are parsimonious.

The offerings that a given student does select, given his life project, and after counseling with his mentors and his parents, will constitute his personal curriculum. The personal curriculum of a student is the set of offerings that he chooses to take.

If the student needs or wants to develop competencies that are not part of the offerings the school makes available, the school ought to make every effort to make it available, either through independent study supervised by the staff or, if needed, through apprenticeship supervised by an outside consultant.

One interesting issue is: must the school require of every student the development of at least a minimum set of competencies (such as basic literacy in the mother language, “numeracy”, mastery of the scientific method, etc.?). The answer is a qualified “yes”. The “yes” is qualified because today it is almost inconceivable that a student will spend about twelve years in an innovative school and not choose to learn how to read and write, how to solve numerical problems, or how to tackle problems of an empirical or theoretical nature. If, even though improbable, a student does not learn how to read and write (for instance) by the time he is eight or nine, his mentors and the pedagogical coordination of the school should have a clear idea of what is happening and of what ought to be done, other than compelling the student to learn.

Something else that is important to consider in this context is the fact that students have different interests and rhythms. A student that learns to read and write at eight might be as proficient in reading and writing as a student who learned to read and write at four, by the time both are, say, twelve. Also, a student who wants to be a poet or a novelist does not need to learn a lot of mathematics, and another, who wants to be a mathematician or an engineer, does not need to learn a lot of syntax or literature.

The active, collaborative, problem-oriented, project-based and research-focused learning methodology that the school ought to adopt is based on the fact that there are many ways of developing essential and important competencies, and that all of these ways can be employed in the form of learning projects, which students, individually or in group, freely choose in order to develop competencies related to their interests (what they want to learn) and, specifically, to their life project (what they need to learn). This methodology respects the students’ freedom to learn and thus solves the vexing and difficult problem of motivation.

Finally, the issue of evaluation. As mentioned above, to be innovative the school must consider evaluation an essential part of the learning process, which cannot be dissociated from it. Evaluation is not a set of specific procedures applied after the learning process has ended, in order to assess whether, or to what extent, the student learned what was expected of him.

If this is so, evaluation cannot be confused with quizzes, tests and exams. Evaluation takes place through observation and interaction, duly registered in a learning portfolium.

If this is so, evaluation cannot be confused with quizzes, tests and exams. The student, together with his mentors, coaches, facilitators and mediators, and, if necessary, also with his parents, must be involved in the process from the very start. The student is not less protagonist when he is evaluating his own learning and his own development along the path of his life project.

Also, the curriculum, if well elaborated, must operationally define the competencies and specify the indicators of its development with different degrees of expertise or depth. This makes it easier to evaluate the learning process as it is happening.

6. An Additional Word on Technology

The school of the Industrial Age was an institution that sought massification of education through standardization. The innovative school that will prepare the path for the Learning Society must seek personalized education that reaches scale through technology.

The next article, the last of this series of four, will deal with technology and how it can make personalized education viable and take it to scale.

São Paulo, on the 22nd of October, 2012, revised in São Paulo, on the 22nd of August, 2017

(*) I thank Microsoft’s Brazilian subsidiary for the authorization to use in this article material that I wrote at her request five years ago.